After setting out a vision for development centred on public transit links, the mayor of London came out of the spending review empty handed. Can London build 88,000 homes a year without new infrastructure? Daniel Gayne reports.

On a hot morning back in May, having taken the train down to Kidbrooke Village in south-east London, I leant over a balcony, halfway up the 21-storey Birch House as I waited for my turn to interview the mayor of London.

Looking out over a sea of crouched brick buildings from this high-rise island of densification, it was clear that the choice of location for Sadiq KhanŌĆÖs big announcement that day was no accident. Density ŌĆō including in previously untouched bits of green belt ŌĆō was the name of the game in the housing strategy he was launching, and underpinning it all were transit links, new and existing.

The vision ŌĆō entitled Towards a New London Plan ŌĆō made clear that transport corridors were expected to provide the spine of development as the capital stretched to reach its aim of building 880,000 homes over the next 10 years.

ŌĆ£The mayor is clear that achieving higher rates of housebuilding also depends on funding for vital transport improvements to unlock additional capacity for these homes,ŌĆØ the mayorŌĆÖs blueprint for development in the capital read. ŌĆ£Higher volumes of development, as well as its sustainability, critically depend on good public transport connections.ŌĆØ

We wonŌĆÖt meet housebuilding targets without investment in transport infrastructure

Jonathan Seager, policy delivery director, research and impact at BusinessLDN

It was assumed, at least by me, that this emphasis suggested that the mayor was expecting something significant in the upcoming spending review. ŌĆ£[Not] unless you know something I donŌĆÖt know,ŌĆØ he told ╬ó├▄╚”, when I asked whether assurances had been given about schemes such as the Bakerloo line extension.

ŌĆ£I see them [government ministers] all the time. They give you no commitments at all.ŌĆØ

Now it rather looks as though the mayor was genuinely blindsided by the subsequent lack of investment in London transport. There was evident fury in his office when, in the days leading up to Rachel ReevesŌĆÖ announcement, it became clear that London would be shortchanged. There was no attempt to disguise KhanŌĆÖs feelings, and briefings to national newspapers made his irritation clear.

The benefits of new transport investment are myriad, and the GLA will have been seeking it for a number of purposes. But the impact on housing in the capital has been underexamined. In a spending review so focused on ŌĆō and generous to ŌĆō housing, did the government undermine its own ambitions by failing to invest in transport?

Jonathan Seager, policy delivery director, research and impact at BusinessLDN, seems to think so. ŌĆ£We wonŌĆÖt meet housebuilding targets without investment in transport infrastructure, undoubtedly,ŌĆØ he says.

Transport links are seen as key to housing delivery essentially because they enable greater density, with a large number of residents able to live in one small area without having to use cars. ╬ó├▄╚” at these urban densities is crucial in a city with a relatively short supply of undeveloped land and will be essential if London is to scale up to building 88,000 homes annually.

ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖve never built anything at that scale ŌĆō not since the 1930s when things were rather different,ŌĆØ admits Tom Copley, deputy mayor for housing and residential development. ŌĆ£Of course, one of the things that they were doing in the 1930s was massively expanding the transport network in London.ŌĆØ

Indeed, the housebuilding boom of the 1930s came alongside major expansions of the Piccadilly line and Bakerloo line after decades of relative stability in the London Underground network.

Now there are lots of ideas for new transit schemes for the capital but, at the spending review, the GLA and TfL were focused on three: the DLR extension, the West London Orbital and the Bakerloo line extension

The DLR extension

The case for the DLR extension, both as a pure transport project and a scheme to boost housing delivery, is perhaps the clearest. The proposed scheme would extend the DLR from Gallions Reach to new stations at Beckton Riverside and, through a tunnel under the river, Thamesmead, connecting two opportunity areas and four development sites.

ŌĆ£From my perspective, as someone who is overseeing housing delivery, my real focus has been on getting that DLR extension,ŌĆØ Copley tells me, describing it as the ŌĆ£best value for moneyŌĆØ of the projects they are looking at.

The scheme is relatively cheap, Copley says, and can be delivered quite quickly once it gets the green light. It could also unlock 30,000 homes.

If funding is secured soon, construction could begin as soon as 2028 and be complete within a matter of years. The GLA is working on proposals for its own contribution, but says it needs some capital contribution from the Treasury.

The route through to delivering Thamesmead is a relatively straightforward one, potentially. No development is straightforward [ŌĆ”] but itŌĆÖs difficult to imagine a more straightforward one

Ian McDermott, chief executive, Peabody

On the housing side, the scheme benefits from the fact that a handful of landlords own much of the developable area around the scheme. Aberdeen Investments owns some sites, the Berkeley Group has land north of the river, but the biggest player is probably Peabody. The social landlord owns vast swathes of land across Thamesmead and, in a joint venture with Lendlease, is developing a masterplan for a huge scheme on a 100ha site called Thamesmead Waterfront.

ŌĆ£We own the land at the moment, and we own the assets and liabilities that go with the majority of the land,ŌĆØ explains Ian McDermott, chief executive of Peabody. ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs no complex land assembly to do in the way that there might be for other projects.

ŌĆ£I think, locally, thereŌĆÖs support for it in a way that, you know, there isnŌĆÖt the opposition. So I think the route through to delivering Thamesmead is a relatively straightforward one, potentially. No development is straightforward [ŌĆ”] but itŌĆÖs difficult to imagine a more straightforward one.ŌĆØ

McDermott estimates that this scheme alone has the potential for about 15,000 homes, with wider development of the providerŌĆÖs site in Thamesmead potentially bringing that up to something like 20,000. But this depends on them being able to develop at urban densities.

For all these reasons, the DLR extension is seen within the GLA as a no-brainer for government backing and had been the great hope going into the spending review. ŌĆ£Anybody thatŌĆÖs looked at these three projects and understands the broader context around them [knows that] hopes were being pinned on on the DLR,ŌĆØ says Seager.

There is optimism among Copley, Seager and McDermott that backing will still ultimately happen, but getting a firm commitment from the government earlier would allow Peabody and others to make early progress. ŌĆ£What we need is certainty, and what we need is commitment,ŌĆØ says McDermott.

ŌĆ£The way I look at the timescales, if we got that certainty within the next few months, ideally, or within the next year, then I think we could get on site, and then we could start on Thamesmead [ŌĆ”] within the parliament.ŌĆØ

Peabody has submitted proposals for Thamesmead to the governmentŌĆÖs new towns taskforce, signifying the scale of its ambition for the area. If it is one of the locations named when the taskforce reports its findings, this will no doubt bolster the case for government investment in the DLR scheme.

Bakerloo line extension

There is also a great deal of opportunity for housing development around the proposed extension of the Bakerloo line. Previously consulted-on plans would extend the existing Underground line from Elephant and Castle to Lewisham, with the potential for further extensions to Hayes and Beckenham Junction.

The mayorŌĆÖs London Growth Plan, published earlier this year, suggests this scheme could unlock around 20,000 extra homes, while Seager at BusinessLDN suggests the number could be as high as 50,000. Some of that larger number, he acknowledges, ŌĆ£you could argue would happen anyway, but quite a lot of them are directly associated with the extension happeningŌĆØ.

Part of the planned extension would run near the Old Kent Road, a major thoroughfare in Southwark which is identified as an opportunity area. According to Copley, the extension is ŌĆ£really important for the continued development of sitesŌĆØ on the road. However, the situation here is more fragmented than over at Thamesmead.

The danger is that, without the transport infrastructure coming, the more developers just say, ŌĆśwell, I canŌĆÖt wait anymoreŌĆÖ

Jonathan Seager, policy delivery director, research and impact at BusinessLDN

ŌĆ£There are a lot of different landowners and developers who have interests along the Old Kent Road,ŌĆØ says Copley. ŌĆ£So the benefits there will be to multiple different developers, be they affordable housing developers, private developers.

ŌĆ£The council also has land and sites along the Old Kent Road. So itŌĆÖs quite fundamental to a lot of schemes coming forward and thereŌĆÖs a lot of development there that is predicated on that additional transport capacity.ŌĆØ

Yet there is a sense in which this complexity creates an even greater sense of urgency. Unlike with the DLR extension, where a single, patient partner has control over the release of land, the myriad owners and developers may have more limited patience.

Seager explains: ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs lots of development interest in these areas at the moment and youŌĆÖre either forcing people to hold back at a time when we absolutely need to get going, or people are choosing to build out schemes, but probably at a lower density and probably overall a suboptimal quantum of homes than otherwise would be the case.

ŌĆ£So the danger is that, without the transport infrastructure coming, the more developers just say, ŌĆśwell, I canŌĆÖt wait anymoreŌĆÖ. I think thatŌĆÖs the particular concern around some parts of the Bakerloo line extension.ŌĆ£

This indeed, is one of the major risks of delaying transport investment in London ŌĆō not that it stops development, but that it means development happens nonetheless, wasting precious land that could otherwise have been developed at higher densities.

West London Orbital

Rounding off the trio of priority projects is the West London Orbital (WLO). This would essentially be a new service on existing but underused rail lines. Running from Hounslow towards Hendon and West Hampstead, the new service would become a part of the Overground network.

According to Copley, ŌĆ£a lot of the infrastructure is already thereŌĆØ, and it is really a question of ŌĆ£joining up and improvingŌĆØ.

Seager says the scheme is ŌĆ£a bit more complicatedŌĆØ, and ŌĆ£far more early on in its planning and its conceptionŌĆØ than the others. He adds that ŌĆ£there arenŌĆÖt as many well developed proposalsŌĆØ for housing growth associated with it. ŌĆ£They are at the stage where they are just trying to work out what it would unlock in terms of housing numbers,ŌĆØ he says.

Nevertheless, provisional estimates published in the growth plan suggest the scheme could unlock 15,800 homes, while Copley points out that there is already a huge amount of development being undertaken by the Old Oak and Park Royal Development Corporations in some of the areas that would benefit from the WLO.

And the restŌĆ”

Beyond the three priority schemes, there are other possibilities for unlocking housing using transportation. One is known as ŌĆ£metro-isationŌĆØ and essentially amounts to increasing the frequency of services on certain existing rail lines to something more similar to that run on the Overground network.

Copley says the measure is ŌĆ£absolutely essentialŌĆØ and will be ŌĆ£particularly essential for the delivery of new townsŌĆØ. The GLA is hoping that at least one, and ideally a few, London sites will be picked by the governmentŌĆÖs new towns taskforce when it announces its findings.

ŌĆ£You have got to be able to get the frequency of train service in order to support the level of density thatŌĆÖs required to deliver development that is not just going to be that low-rise, car-heavy dependent,ŌĆØ says Copley, describing metr-oisation as ŌĆ£a key ask of the mayorŌĆØ and pointing to the success of the Overground.

He says there is an opportunity to take advantage as the government nationalises franchises, but it is ultimately ŌĆ£a decision for DfTŌĆØ.

Of metro-isation, Seager says: ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs kind of lingering in the background. There was a bit of push a while ago, [but] the government didnŌĆÖt show a huge amount of interest. I think itŌĆÖs yet to be kind of pushed at again with this government, but there is an opportunity there.ŌĆØ

One way or another, though, Seager says suburban London will need to be densified, and it will need the transport links to enable that.

The GLA has been tight-lipped about which areas have made submissions for intra-London new towns, but ╬ó├▄╚” understands that sites in north-east London have been put forward. There are existing rail links to this part of the capital but, if a major new town-scale development were delivered here, it would strengthen the case for a similarly large new infrastructure investment.

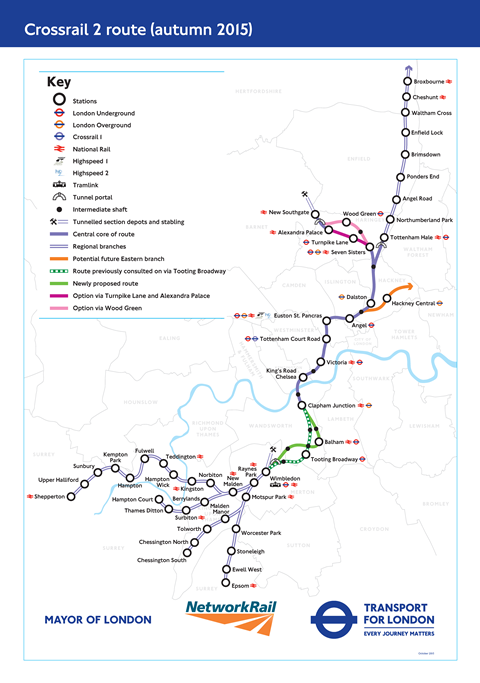

It is hard not to think of Crossrail 2, proposed routes for which typically follow the loose path of the River Lea, through Hackney, Haringay, Enfield and beyond.

In the longer term, this scheme remains the great hope for many in the capital. The project would be a major new north-south on the scale of the Elizabeth line, creating a cross-capital link between Surrey and Hertfordshire.

ŌĆ£When itŌĆÖs time comes ŌĆō and it will eventually ŌĆō then I think that will be a scheme which truly could deliver the scale of growth in terms of housing numbers that we need,ŌĆØ says Seager.

According to the growth plan, an estimated 200,000 new homes could be unlocked by the scheme, although Seager says the city will have to do a better job on seizing the opportunity than they did on its predecessor scheme, where associated housing delivery happened ŌĆ£organicallyŌĆØ rather than strategically.

ŌĆ£If you had taken some of those decisions before you started constructing, or indeed perhaps stepped in as you are constructing, and thinking about what that means for local plans, what that means for potentially delivery vehicles associated with such as creating development corporations, then maybe we would have got even more of a development dividend from that project.ŌĆØ

So, what next?

There was one small fig leaf for new London transport infrastructure in ReevesŌĆÖs spending review ŌĆō a Treasury document in which the government says it ŌĆ£recognises the potential growth and housing benefits of the Docklands Light Railway (DLR) Thamesmead extensionŌĆØ and committed to working with TfL to exploring options for delivery.

ItŌĆÖs not much, but it indicates that the capital might not have to wait too much longer for backing for the scheme.

Seager says this does not have to take the form of cold, hard cash, explaining that there are ŌĆ£lots of different waysŌĆØ the government could help with funding.

ŌĆ£This is where we were hoping that the spending review could, in particular, push the DLR a bit further along the line,ŌĆØ he says, suggesting that guarantees, loans or even more creative solutions could be found ŌĆō for instance by directing affordable homes grants to unlock housing schemes around new stations in exchange for developer contributions towards the infrastructure itself.

He also raises tax increment financing, as was used to fund the Northern line extension, as a potential model. This would allow TfL to borrow in order to fund the scheme, with repayment coming from growth in business rates within an outlined area.

The problem is that, for all of these models, central government would need to get involved. ŌĆ£ThatŌĆÖs what we were hoping for in the spending review,ŌĆØ says Seager.

ŌĆ£If central government isnŌĆÖt going to directly fund things or support them in some way, what it needs to do is devolve the competencies to London government, or the borrowing power to London government, to let London lead on some of these decisions.ŌĆØ

No doubt there is frustration among those keen to get London building, but the situation is not yet one of despair. As Seager says, the spending review was an opportunity for the government to back the capitalŌĆÖs growth ambitions. ŌĆ£It hasnŌĆÖt,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£But there will be other opportunities.ŌĆØ

No comments yet