Nicholas Hare Architects was faced with an unusual set of challenges in its refurbishment of UCL’s Bloomsbury Theatre, which is wrapped around by a variety of other university facilities that had to remain open during works.

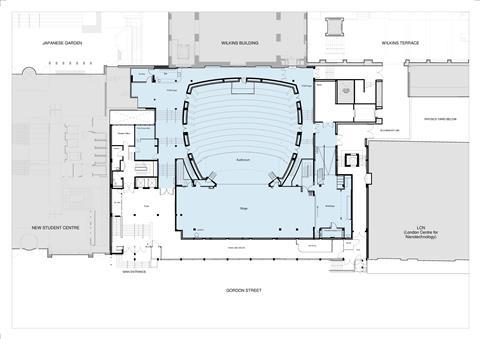

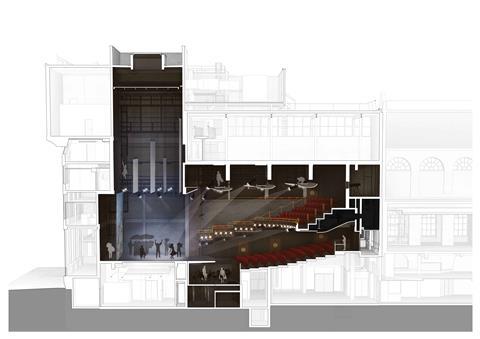

Perhaps only in the 1960s would anyone have placed a gymnasium, squash courts, snooker halls and a series of rowing tanks above a theatre auditorium … and then surrounded it on three sides by a university, with a student refectory squeezed in underneath for good measure. Such is the structural stranglehold by which London’s Bloomsbury Theatre finds itself constrained – one that an ambitious new £12m refurbishment scheme by Nicholas Hare Architects has now done its best to unlock.

The Bloomsbury Theatre was designed, with apparent multifunctional zeal, by architectural practice James Cubitt & Partners in 1968. As the University of London goes, it is a fairly restrained example of brutalist design, with an arched brick and concrete facade supporting a blank, cantilevered attic storey.

The theatre’s name at its time of opening was the Central Collegiate ��Ȧ, which explains its multipurpose composition: it was essentially established as a combined recreational facility for University College London, now known as UCL, which owns the building and within whose loosely defined Bloomsbury campus it is located. While the facility provided the aforesaid sports facilities on its upper floors, its showpiece was the 550-seat theatre on its lower levels, after which the entire building was renamed in 1982.

UCL has never offered courses in drama or theatre studies, so this lavish facility was and is used purely for extracurricular productions – both student shows and independent productions unrelated to the university, ranging from West End shows to stand-up comedy nights. Over the decades it has built up an affectionate fanbase both within and without its academic environs.

The original building, however, had some very obvious drawbacks. These included a small, congested entrance and limited bar and foyer space, not to mention the immense structural and mechanical complexity consequent on having a theatre sandwiched between a diverse range of other building types and functions. As Nicholas Hare associate Andrew Hayes points out: “It’s like a huge sandwich where there’s tonnes of bread.”

It is these shortcomings – along with the updating of the theatre’s rather dated fixtures and fittings – that have been addressed in the new refurbishment, which was unveiled at the Bloomsbury Theatre’s reopening last month.

Read similar case studies, including:

Site challenges

The refurbishment project was made all the more challenging because the limited access allowed by the theatre’s centre location within the building meant that all construction materials had to be brought in through a single door in the basement. Another difficulty was the need to keep all the spaces around the theatre operational throughout the project.

This latter challenge was further complicated by the fact that, in another example of its convoluted 1960s composition, the building’s two fire escapes were shared with neighbouring buildings so had to remain accessible throughout. One of these buildings is UCL’s new Student Centre, which opened last month and was concurrently designed by the same architect (see “The build next door”, below).

But the biggest challenge of all involved the renewal of all the theatre’s convoluted services while not interfering with those services that served other parts of the same building. Nicholas Hare’s Hays says: “We replaced the theatre’s entire services and this was probably the single biggest challenge of the project.

“It required us to undertake a significant amount of work that involved us trying to understand the extent of historic and redundant services, as well as the live ones which crisscrossed the theatre yet fed other parts of the building and therefore had to be kept live.”

But the mammoth services overhaul is not at all evident when first entering the building. The foyer has received a light-touch refurbishment, with new satin-matt polished brass stair rails and ventilation grills very much retaining the spirit of the 1960s. The major change to the foyer area has been the relocation of the bar to provide more efficient use of the space – a relatively minor change that is nevertheless said to have already enabled the bar to double its takings.

While the main auditorium too retains the visual spirit of its 1960s inception, there is more evidence here of modern alterations and additions. The continental seating rake has been retained: namely a configuration of curved seating that allows longer continuous rows before the introduction of a central aisle is required – an allowance essentially created by installing greater legroom. The Bloomsbury Theatre was one of the first in the UK to be fitted with such seating.

New acoustic panelling in the walls comes in the form of black-painted tulipwood, while new auditorium doors, balcony fronts and the proscenium arch are treated to American black walnut to provide a subtle contrast. The wood in turn contrasts with the reappearance of satin-matt finished ironmongery and metalwork and the reupholstered plush red seating of the stalls.

The build next door

At the same time that Nicholas Hare Architects was proceeding with the refurbishment of the Bloomsbury Theatre, the practice was in the unusual position of working on an entirely separate project next door. Built by Mace, UCL’s new student centre opened last month shortly after the theatre, and although both buildings share a fire escape staircase, they are very different projects.

The student centre is a new-build scheme and, unlike the theatre, has a sizable external impact. The £67.4m eight-storey facility provides 1,000 study spaces centred around a striking atrium and comes complete with a roof terrace and a landscaped central courtyard partially enclosed by an elegant new colonnade. With a BREEAM Outstanding rating, it aims to be one of the UK’s greenest university student centres.

Unlike the brutalist Bloomsbury Theatre, the new building casts a far more conciliatory heritage tone, with handsome, ordered facades of reconstituted stone and buff brickwork responding sensitively to their historic conservation area context. But the two buildings do have one significant thing in common: they both contribute to the complex network of routes, subterranean spaces and interlocking courtyards that constitute much of the UCL Bloomsbury campus and tie together its disparate collection of classical and modern buildings.

Technical and services

As is often the case in refurbishment or restoration, evidence of technical and services upgrading is largely hidden from view regardless of how extensive the transformation has been. But the first clue about these elements of the project come with the three new GRG (glass reinforced gypsum) acoustic reflector panels installed on the ceiling of the auditorium.

These were installed via a scaffold and hoist system erected on the auditorium floor during construction. As well as serving an acoustic function, they help partially conceal the massive concrete-encased steelwork truss that forms the roof of the theatre and supports the massive loads from the remainder of the building above it. Interwoven around the truss but largely invisible from the auditorium below is a labyrinth of new cabling, trunking and ductwork that indicates the services overhaul that has taken place.

Previously these were only accessible via a complicated and dangerous hoist and harness mechanism. But new steel walkways have been installed to meet modern safety standards. The services themselves are remarkable in their complexity. There were four types of services to be considered. The first did not relate to the theatre at all but passed through it to serve the remainder of the building. The second, third and fourth all related to theatre-specific servicing and included stage lighting, audiovisual and stage engineering respectively.

Of the four stages, stage engineering had the most clearly defined and simple routes and was therefore, in Hay’s words, “the least onerous to manage”. This was not the case for the other three, where there was a significant amount of overlap – and, in the case of lighting and audiovisual, redundancy – which required careful replacement of components.

Replacing and untangling all these services was done with the help of a sophisticated BIM model, as Hays explains. “As a starting point a survey model was produced, which was developed further based on original built drawings. Strip-out during enabling works also led to a better understanding of hidden elements. Existing services were modelled and brought in to allow co-ordination across all disciplines, and a set of point clouds were introduced to indicate locations where work was taking place and could be viewed within the model.”

Delivering the principle of containment created another complication. Some of the new trunking installed is of a significant size and in some instances required trunking boxes almost half a metre wide. Ensuring audiovisual, lighting and stage engineering were kept separate from each other was a process that Hays describes as the “hardest” element of the project to achieve but one again realised with the help of BIM.

“Between these types of containment there were specific rules requiring a degree of separation to ensure there wasn’t interference which would impede the stage engineering equipment or operation in a performance condition. In order to manage this the design team and contractors worked in BIM to ensure the separate models could be linked together and co-ordinated while achieving the separation needed as part of the design requirements,” he explains.

As part of the services overhaul, some services were diverted along new routes, to the benefit of other parts of the building beyond the theatre –such wider technical overlaps being characteristic of the project. A new service riser that was added to the rear of the theatre also accommodated a more efficient variable-temperature heating system serving the radiators in the gym above and replacing its outdated constant-temperature heating system. And a new ventilation system for the existing back-of-house toilets connected to a new rooftop plant enclosure also served the showers and toilets for the gym.

Other significant elements of the theatre’s refurbishment involved the installation of two new orchestra pit lifts, new back-of-house and dressing-room facilities and safer improved access to the flytower and theatre workshop beside the stage. The latter two areas are separated by a gigantic, seven-tonne sliding metal door measuring 6x7m and capable of delivering production-standard acoustic insulation levels of 55 decibels. In order to ensure the door fitted through the limited basement access point, it was brought into the site in parts before being assembled in situ.

But the real legacy of the new Bloomsbury Theatre is the complexity and sophistication of its mammoth new services, which not only were required to be hidden from public view but also rely on containment being achieved between individual elements and those services serving other parts of the building. It makes plain the realisation that in order to maintain the illusion of theatre, a considerable amount of technical reality is working away behind the scenes.

Project team

Architect: Nicholas Hare Architects

Main contractor: Overbury

Structural engineer: Integral Engineering Design

Services engineer: Max Fordham

Cost consultant: Aecom

Theatre consultant / acoustic engineer: Charcoalblue

Project management: Arcadis

No comments yet